Insetting is emerging as a powerful way for companies to cut emissions where it matters most: inside their own supply chains. But to make credible emission reduction claims, companies must understand how chain-of-custody models and market-based mechanisms enable (or limit) these claims. This article breaks down the different models, what they mean for insetting, and how to choose the right approach based on your supply chain and ambition.

What you will find in this blog:

- Insetting means reducing emissions inside your supply chain.

- You need traceability to claim the impact.

- Chain-of-custody models define how this traceability works.

- Some models are stricter; others (like book & claim) are more flexible.

- We explain how to choose a model and what each enables.

Introduction to insetting

Insetting focuses on reducing emissions within your own supply chain, where it matters most, with the effect that it reduces your Scope 3 emissions and those of your supply chain partners. This is different from offsetting, which compensates for emissions through external projects Insetting is an instrument to realize SBTi emission reduction targets.

What is insetting and how do you prove the impact?

Insetting can take many forms, which unfortunately doesn’t make it easy. In the end, it’s about making a change happen in your value chain: less emissions and therefore, less global warming.

Changing things costs money, so incentives need to be aligned to make that happen.

One of the incentives is being able to report on the improved footprint of a project or product and make a credible claim about it. In order to do so, two forms of proof need to be there:

- Be able to prove causality between the change that happened and the source of capital (the actual co-financing).

- Be able to show that the improved footprint actually is part of your supply chain.

The definition of what is part of your supply chain is the cause for lots of confusion (and discussions). Because supply chains are complex, especially in the agri-food sector.

A typical way of defining supply chains is using the concept of chain-of-custody. Chain-of-custody refers to how materials or products move through a supply chain, and how their origin and characteristics are tracked or documented along the way.

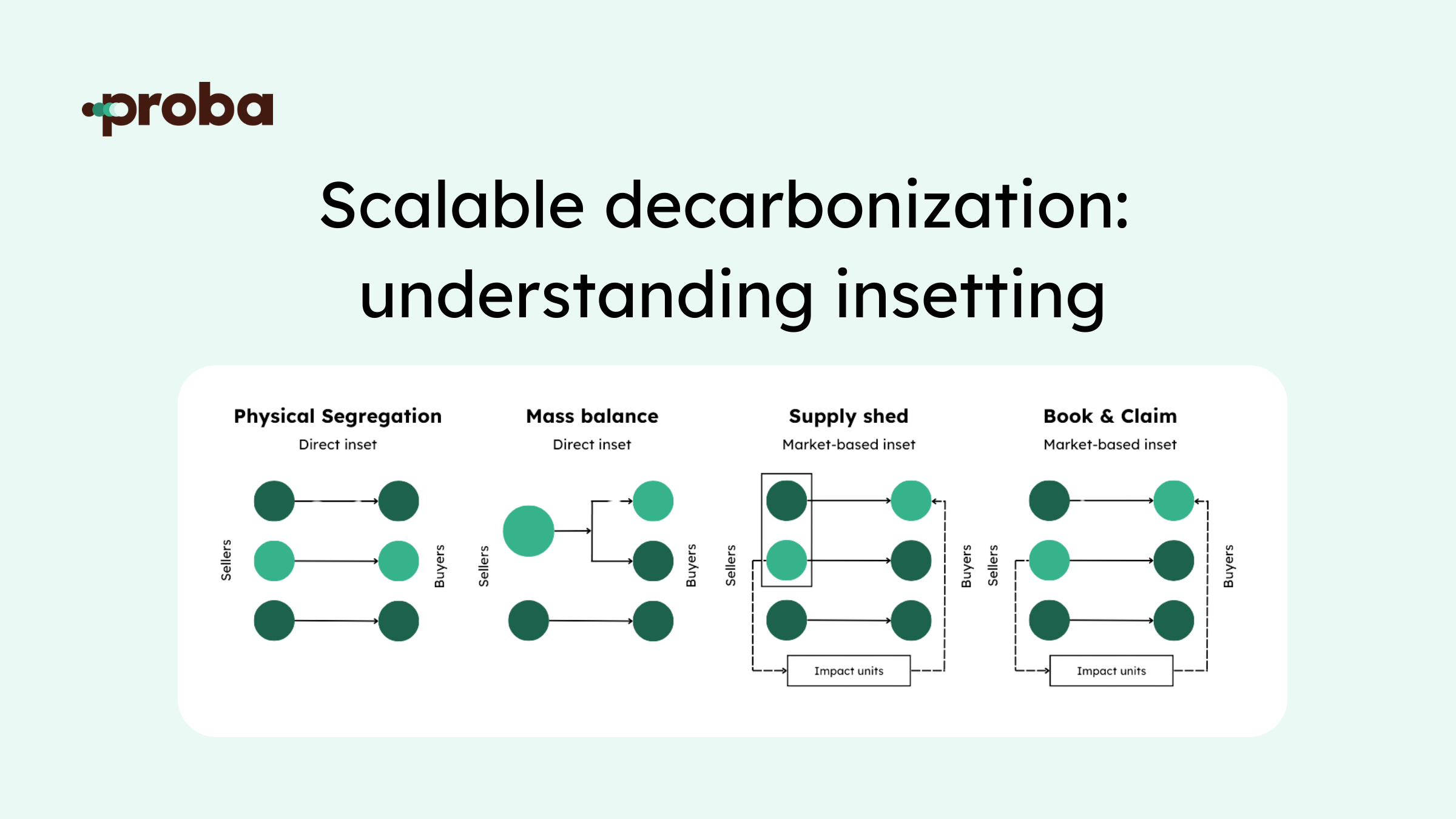

To credibly prove emission reductions within your supply chain, you need a method to trace these reductions. ISO 22095 recognizes five chain-of-custody models:

-

- identity preserved model: materials or products originate from a single source and their specified characteristics are maintained throughout the supply chain;

- segregated model: specified characteristics of a material or product are maintained from the initial input to the final output;

- controlled blending model: materials or products with a set of specified characteristics are mixed according to certain criteria with materials or products without that set of characteristics resulting in a known proportion of the specified characteristics in the final output;

- mass balance model: materials or products with a set of specified characteristics are mixed according to defined criteria with materials or products without that set of characteristics;

- book and claim model, including supply shed based models: the administrative record flow is not necessarily connected to the physical flow of material or product throughout the supply chain; a supply shed sets a boundary (definition of supply chain for the reporting company) within which book & claim can be applied;

Here’s why these models matter for insetting: they provide a framework on how to establish that the improved footprint of a project or product is actually part of your supply chain.

To make matters more complex, not all chain-of-custody-models are created equal in the eyes of the ESG auditor or the GHG accounting and reporting standards. Some are more equal than others. For reporting companies conforming to SBTIi, more clarity is on its way. SBTi just came out with the draft v2.0 version of its Corporate Net-Zero Standard.

Based on this draft, it will acknowledge the challenges related to traceability and data quality in these chain-of-custody models (and hence the underlying supply chains) and it will introduce the concepts of direct and indirect mitigation.

The word “mitigation” can, with some mental flexibility, be replaced with “insetting”. So now we have direct insetting and indirect insetting.

- Direct mitigation/insetting allows for claiming intervention benefits (emission reductions) for most of the chain-of-custody models, including at the activity-pool level when direct traceability to specific emission sources is not feasible.

- Indirect mitigation approaches (e.g., book-and-claim commodity certificates) where direct traceability is not possible or where persistent barriers prevent mitigation at the source are possible as well.

Note that only the supply shed and book & claim models require (!) certification and/or tradable certificates to be able to claim the emission reduction in your supply chains. The other models could benefit from (independent) certification as well, but do not require this. Usually, some form of assurance is needed.

These chain-of-custody models and market based mechanisms offer companies more (or less) flexibility in implementing sustainability solutions while maintaining credibility in their emissions reduction claims. This flexibility can help decarbonization in supply chains in two main ways:

- Most importantly, it can help find willingness to pay. Some companies are more ambitious than others when it comes to reducing their supply chain emissions. Your direct customers may not be looking for scope 3 emission reductions. And vice-versa, it may be challenging to have (all) your direct suppliers implement sustainability solutions.

- Another benefit is more practical. Supply of low carbon fertilizer (technologies) is not always available in certain markets. More flexible market based mechanisms such as book&claim allow ambitious companies to invest in decarbonization without the constraints of the physical supply. This also helps create a market for these products in the first place. Often the reporting company looking to reduce scope 3 is far away in the supply chain from the producer offering a sustainability solution (e.g. a food company vs a fertilizer producer)

|

Some examples to make the above models more clear Physical Segregation A food company supports farmers from which they source crops, to apply nitrogen stabilizers to reduce fertilizer emissions. The company claims these reductions as part of its sustainability strategy. Mass balance A farmer coops sources 10% of its nitrogen based on green ammonia. The green fertilizer is mixed with conventional fertilizer and not separately processed to the farmer, but the lower footprint is allocated to specific farmers (of course adding up to the same amount sourced). Supply shed A retailer sources grain from a specific farming region for specific crops where many producers use nitrogen stabilizers. The retailer can include the region’s overall emission reductions in its sustainability reporting. A food company funds nitrogen stabilizer programs in farming areas outside its direct supply chain. It receives certified carbon reduction credits in return. |

Closing thoughts

The flexibility of insetting makes it easier for reporting companies to align sustainability strategies with emissions reduction goals. In the case of fertilizer producers, insetting allows them to get rewarded for low carbon solutions when there is insufficient market efficiency. Whether working directly with farmers, collaborating through intermediaries, or leveraging market-based approaches, businesses can integrate decarbonization solutions in ways that will suit them.

Interested in exploring insetting opportunities for your supply chain?